Artist/Educator Archive Interview - Drs. George and Susan Dersnah Fee |

|||

e regularly feature the personal experiences and insights of a noteworthy artist/educator on various aspects of piano performance and education. You may not always agree with the opinions expressed, but we think you will find them interesting and informative. The opinions offered here are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily represent those of the West Mesa Music Teachers Association, its officers, or members. (We have attorneys, too!). At the end of the interview, you'll find hypertext links to the interviewee's e-mail and Web sites (where available), so you can learn more if you're interested. Except where otherwise noted, the interviewer is Dr. John Zeigler.

|

|||

|

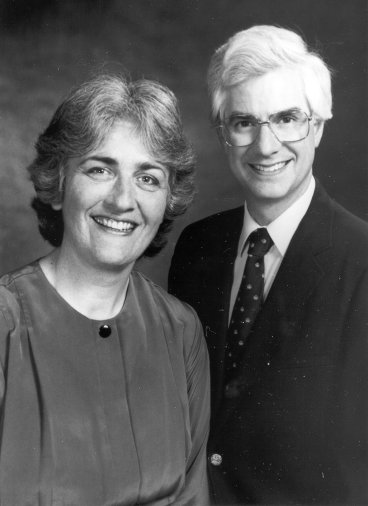

The September 1999 artist/educators:

We each went into music for very similar reasons: a love of the emotional content and sound of the music, a means of spiritual expression, the challenge of searching for a means of expressing something higher than ourselves, and the desire to share the greatness of music with others.

George--My teacher from ages 6-18 was Willis Bennett, in Washington, D.C. He was the

model of a caring teacher, and was a wonderful role model for me as a boy. He shared his

own enthusiasm for music, his love of beautiful piano tone, and was a joy to be with. He

is the main reason I became a music teacher.

The greatest joy in performing is becoming immersed in the sound, and trying to share with the listener a vision of the greatness of the music. As a teacher, a great joy is feeling that one has found a key for a particular student that has unlocked some aspect of the music that they have been striving for. The greatest joy is often when that happens with a student who is less naturally gifted.

Some of most common problems: inconsistent preparation; lack of a concept of tone, shape, direction, rhythmic underpinning, overall plan for the piece; physical stiffness and lack of proper arm usage; not listening to oneself while playing.

Try to avoid: playing too fast (especially when hesitations and stumbles result), starting without conceiving of tone and tempo first, and giving talented students repertoire that is too difficult too soon.

Listen to yourself. Pre-hear the sound you will make, and set a tempo in your mind that you can play without struggling. Keep your music-making a joy, and a way to express yourself.

Freely exhibit your own love of music--transmit an appreciation for its greatness, spiritual depth, and profundity. Individualize your teaching so that each students' personal needs are being met, and that each student knows you care deeply about him/her as a person.

Music is not just a job, it is a way of life. While it has great long-term fulfillment, it also has many short-term frustrations. It requires such complete commitment and sacrifice that if any other career seems acceptable, music should be your avocation. If the calling is so great that it is the only satisfying choice, then give it everything you have.

It takes the desire and ability to convey the love of music and of humanity, stubborn persistence, mental strength and endurance, patience with oneself and others, perpetual enthusiasm, common sense, and the knowledge of who your student or audience is.

Competitions are actually an unnatural part of music making, but have become a necessary evil in our modern society. The key for younger students is, as it is in all music study, the parents. If parents have a wholesome attitude, then contests can be a character-building, positive experience. The goal can help focus preparation of repertoire, and the performance experience can help prepare for later challenges in life. Everyone must realize that the results are capricious. The best advice for dealing with them is: expect the unexpected. Well-credentialed judges often don't agree with each other, and deserving people are often left out of the winners' circle. Young students mature at different rates, and picking a "winner" is often very arbitrary. Results say little about the students, but show how subjective human beings' responses are to musical performance. The winning, for young people, is the accomplishment of meeting the goal and performing to the best of one's ability on that day.

Master classes for college students can be extremely beneficial. There should be far more of them, to supplement an experience that often results in four years of only one teacher's ideas. Master classes for younger students can be more problematic, and often fail to provide lasting results. Sometimes the young student, while courageous in appearing, is not responsive. Very often organizers schedule too many students and insufficient time to really help each student. Some teachers may also use attendance at master classes as a continuing education substitute for much more beneficial private study and personal practice. And, of course, the success of a master class is largely dependent on who the "master" is. We, ourselves, try to provide specific concepts and tools, which can then be applied by

the player and the audience to other music, as well. We try to inspire the player and

audience, at the same time that we are giving "nuts and bolts" specific advice.

Rather than re-address the same issue with multiple students, we try to cover a number of

musical and pianistic areas. We also reinforce things the student is doing successfully,

and valuable concepts the teacher has obviously told the student already, giving the

teacher due credit. The exciting challenge in giving a master class is to make every word

really count. In a small amount of time, one must supportively put one's finger on what is

most in need of help, and what the specific solution might be.

Teaching--Best: When a student has a moment of realization that has been arrived at together with the teacher, and the thing that we've been striving for suddenly happens and makes sense. Transcending the joys in the studio, is the fulfillment we have felt from having helped raise a generation of children, and supported fellow adults through crises in their lives. The testimonials from them, the Mother's and Father's Day cards and flowers, and the opportunity to be in their weddings are some of the beautiful and meaningful responses from them which we will always treasure. When they are young, they appear at the door with their gerbils and puppies. When they get older, they appear with their children and grandchildren. Sharing all of these, and other significant moments, is a special joy to us. Worst: Teaching students who disrespect the music by preparing poorly and not putting forth effort Performing--Best: When one loses oneself in the music and the "self" gets out of the way. Worst: When the awareness of "self" intrudes to distract and raise doubts about memory.

The teacher can provide enthusiasm and love of the child, trying to pull out the individuality of each child. We can also help lead them to use the piano as a means of self-expression throughout their lives. But the parents must assume the responsibility for controlling distraction, whether in the practice environment or in limiting the number of activities the child undertakes. Too many teachers feel it is their failing if a child is overcommited and doesn't achieve good results in music. Ultimately, the teacher is powerless to counteract what the parents fail to control.

We are attracted to musicians who create a beautiful sound, know how to shape a phrase and make it breathe, and become personally involved in the immediate, spontaneous communication of the message of the music. We have heard this done by elementary and teenage students, when many of today's "name" artists can disappoint. Live performances by Rubinstein (as opposed to his often unexceptional recordings) were a major inspiration in our youth. Most of our favorite pianists are older or dead. The legendary pianists born in the 19th and very early 20th centuries ought to be required listening for every teacher and student. The legendary pianists exuded a natural, spontaneous joy in music-making, and had an intuitive, effortless ease of communication when they spoke, breathed and sang through the instrument. Their approach was especially well-suited to 19th century music, the heart of the piano literature, and, to our ears, has not been frequently equaled since. However, it is easy to get caught up in nostalgia for the past. The legendary pianists rarely played Bach, Haydn, and Mozart, and when they did, it usually wasn't their strong suit. It is common today to find superb performances of these composers' works. Today's pianists also can perform the most complex 20th century works with much insight. The number of outstanding pianists in the world today is astounding. The quality of piano teaching at all levels in today's world is also at an extraordinarily high level, compared to the past. Every college faculty has well-trained DMA's, and few children live very far from someone who can give a sound technical and theoretical foundation. Therefore, in most respects, today's world of piano playing and teaching is a great advance over any previous time. However, in 19th century literature, we think we were ideally served by the older pianists, who didn't succeed via the competition route, but who earned their careers via audience communication, and were hired by presenters who sought artists who communicated simply and directly to the hearts of listeners.

We can bring music to children where they are, but more importantly they have to be exposed to a musical environment in their homes. Parents must involve their children with good music. People who make up concert audiences today were taken to concerts as children. Parents must be educated to the fact that if they are "too busy" to take on this responsibility, then our musical heritage will die. There will be no audiences of the future.

Share your joy in music by taking lessons yourself. Be willing to spend the money for supplies that you need to be a professional musician--books, CD's, convention fees, lessons. Charge enough to get the continuing education you need--have a printed studio policy so that you won't be inadvertently abused. Don't be afraid to promote yourself in your new location. No one has all the answers--you learn by doing. Provide goals for your students--studio classes, recitals, achievement programs, etc. Join professional organizations of teachers. Talk about your frustrations--YOU ARE NOT ALONE.

Joys: starting a new student; seeing someone's life be changed by music; watching a person blossom as he/she grows in ability and self-esteem; having long term relationships with students. Frustrations: families with too many activities; students who have no concept of personal discipline; bookkeeping, billing, music ordering; financial challenges of self-employment--insurance, pensions, etc.; lack of time for practice/personal renewal.

Yes, organizations are important. They need to address the problems of the average teacher. There is often a temptation to allow them to become a showcase for talented students of 10% of the teachers, who have 90% of the talented students. As a result, many of the teachers often can't relate. Teachers must attend meetings and conventions, ask for what they need, and not be afraid to speak up. Be active--the more you give, the more you get.

Students: It is never too late to learn an instrument. Adults can

accomplish so much, even if they have never played an instrument. Their main challenge is

to be patient with themselves. Perhaps local orchestras could engage more outstanding local and regional artists. Perhaps state arts councils could find a way to advertise the playing of more pianists. Why don't they set up a comprehensive list on a web site of pianists who are available for public concerts in their states? If they can't or won't, some other state or national group should provide such a list, e.g. the state music teachers association or the national MTNA. We are not suggesting that they endorse the quality of performance, or provide grants. It just seems someone, or some group, should facilitate matches between independent artists, who have spent their lives perfecting their skills, and who are available to perform, but don't have major management, and those institutions or locations which are in need of more classical music concerts. You can ask your own questions of the Fees by e-mail to sdfee@cox.net and learn more about their studio and teaching at their Web site: http://www.dersnah-fee.com/ |

||

|

Page

created: 9/1/99 Last updated: 02/02/24 |

George Fee received his doctorate in piano performance from Indiana University,

where he was a student of Menahem Pressler. Having begun his collegiate study at the

Eastman School of Music, he earned his bachelor's degree from the Oberlin College

Conservatory and his master's degree from the University of Wisconsin. Dr. Fee has

performed numerous solo recitals throughout the country. He has always been an avid

student of music history. His doctoral dissertation, The Solo Keyboard Sonatas and

Sonatinas of Georg Anton Benda, is a major resource in the field of 18th century music. In

more recent years, he has investigated the fundamentals of piano technique to determine

means of preventing and curing pianistic injury.

George Fee received his doctorate in piano performance from Indiana University,

where he was a student of Menahem Pressler. Having begun his collegiate study at the

Eastman School of Music, he earned his bachelor's degree from the Oberlin College

Conservatory and his master's degree from the University of Wisconsin. Dr. Fee has

performed numerous solo recitals throughout the country. He has always been an avid

student of music history. His doctoral dissertation, The Solo Keyboard Sonatas and

Sonatinas of Georg Anton Benda, is a major resource in the field of 18th century music. In

more recent years, he has investigated the fundamentals of piano technique to determine

means of preventing and curing pianistic injury.